Celiac disease is a chronic, hereditary autoimmune disorder where the ingestion of gluten triggers an immune response that damages the small intestine. This reaction specifically targets the villi, impairing nutrient absorption. Unlike a food allergy, it is a lifelong condition requiring strict adherence to a gluten-free diet to prevent severe systemic complications.

What is Celiac Disease and How Does It Differ from Allergies?

Celiac disease, also known as celiac sprue or gluten-sensitive enteropathy, is a multisystemic autoimmune disorder. It is crucial to distinguish this medical condition from non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and wheat allergies, as the physiological mechanisms and long-term risks differ significantly. While a wheat allergy generates an IgE-mediated histamine response (classic allergic reaction), celiac disease involves an IgA and IgG-mediated autoimmune assault on the body’s own tissues.

When an individual with celiac disease consumes gluten—a protein complex found in wheat, barley, and rye—the immune system misidentifies the gliadin peptide fractions of gluten as a threat. Instead of simply neutralizing the foreign protein, the immune system attacks the lining of the small intestine. This distinction is vital for patients to understand because even microscopic amounts of gluten (cross-contact) can trigger the autoimmune cascade, whereas those with intolerances might tolerate small amounts without tissue damage.

How Does the Autoimmune Response Damage the Intestine?

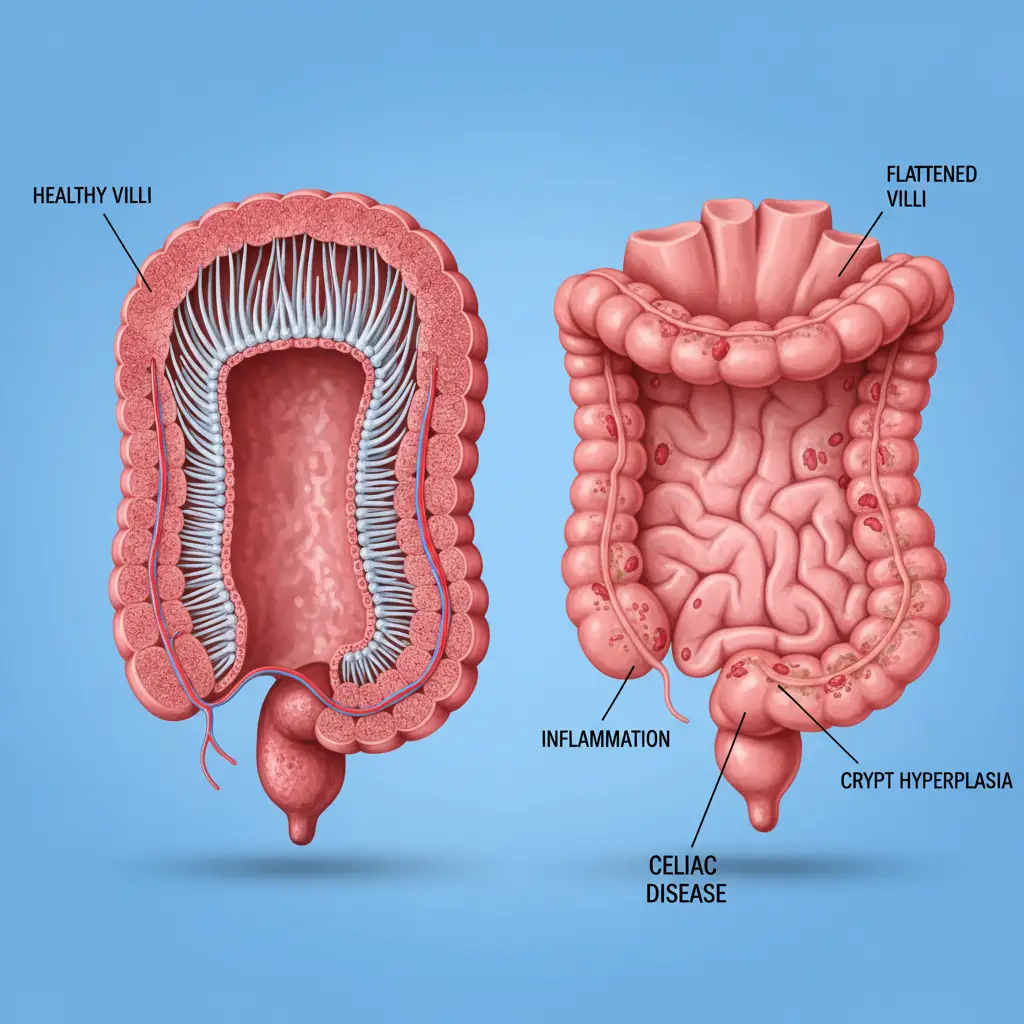

The pathology of celiac disease centers on the small intestine, specifically the mucosa (lining). The healthy small intestine is lined with millions of microscopic, finger-like projections called villi. These villi significantly increase the surface area of the intestine, allowing for the efficient absorption of fluids, electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals.

The Role of Tissue Transglutaminase (tTG)

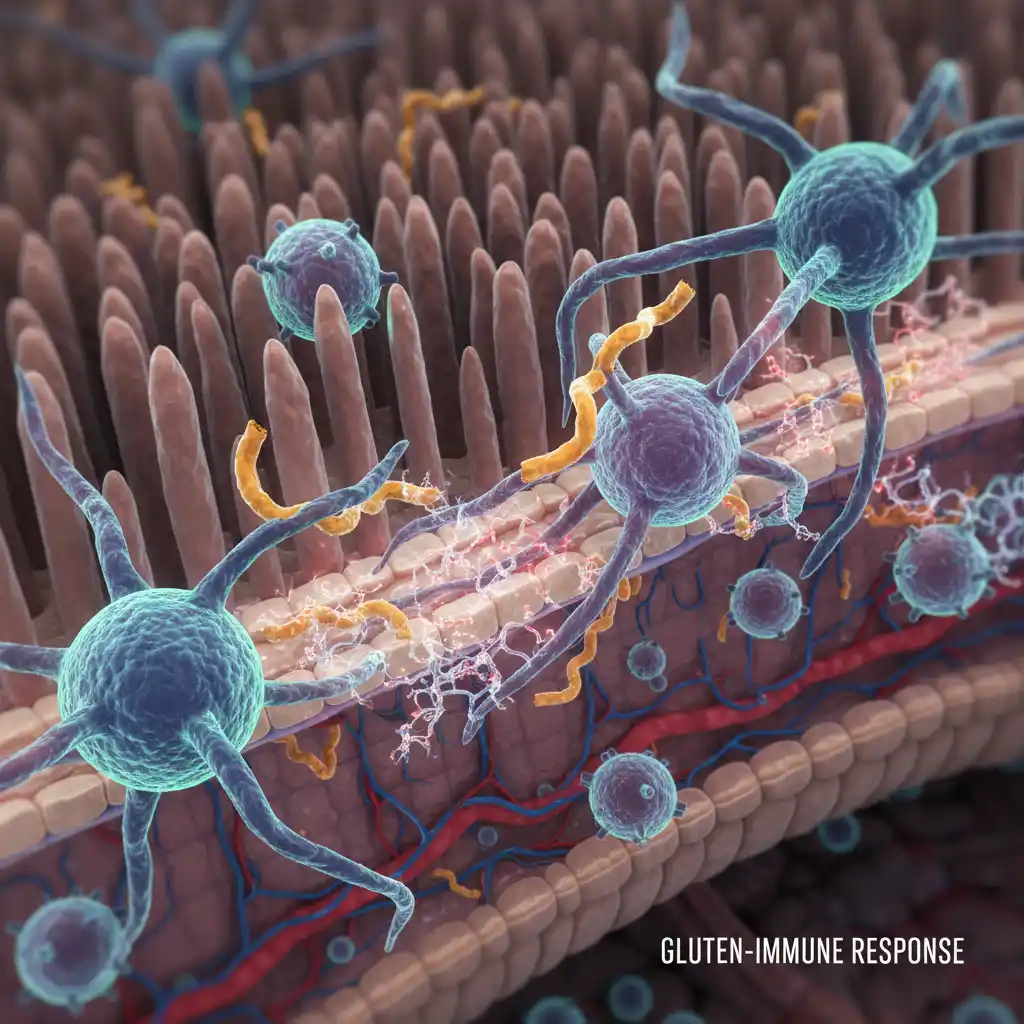

The autoimmune process is complex. When gluten is ingested, it is broken down into peptides, including gliadin. In celiac patients, these gliadin peptides pass through the epithelial barrier of the intestine. Once inside the tissue, an enzyme called tissue transglutaminase (tTG) modifies the gliadin. In individuals with the genetic predisposition for celiac disease, the immune system’s antigen-presenting cells bind avidly to this modified gliadin.

This binding activates T-cells, which then signal the release of inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines cause destruction to the enterocytes (intestinal lining cells) and stimulate B-cells to produce antibodies against the body’s own tTG enzyme. This is why anti-tTG antibodies are a primary marker used in diagnosis.

Villous Atrophy and Crypt Hyperplasia

The cumulative effect of this inflammation is “villous atrophy.” The villi become blunted or completely flattened. Simultaneously, the crypts (valleys between the villi) may elongate, a process known as crypt hyperplasia. When the villi are flattened, the functional surface area of the intestine is drastically reduced. This leads to malabsorption, meaning that no matter how much food the patient eats, their body cannot absorb the essential nutrients required for health. This mechanism explains why untreated celiac disease often leads to malnutrition, weight loss, and specific deficiencies like iron-deficiency anemia.

What Genetic Factors Cause Celiac Disease?

Celiac disease is fundamentally hereditary. It does not develop unless an individual carries specific genetic markers. The primary genes involved are located on the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) complex. Specifically, the variants HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 are the key determinants.

Approximately 95% to 99% of people with celiac disease carry the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 gene. However, having the gene is necessary but not sufficient for the disease to develop. Roughly 30% to 40% of the general population carries these genetic markers, yet only about 1% of the population develops celiac disease. This suggests that other environmental factors—such as viral infections, gut microbiome composition, or the timing of gluten introduction in infancy—may act as triggers that switch the gene “on.”

Because of this strong genetic link, first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) of a diagnosed celiac patient have a significantly elevated risk—approximately 1 in 10—of developing the condition themselves. Medical guidelines recommend that all first-degree relatives be screened for celiac disease, even if they are asymptomatic.

What Are the Symptoms of Celiac Disease?

The clinical presentation of celiac disease is notoriously variable, earning it the nickname “the clinical chameleon.” Symptoms can appear at any age, from infancy to late adulthood, and can affect almost any organ system.

Classic Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Historically, celiac disease was thought to present primarily with digestive issues. These “classic” symptoms are more common in young children but affect many adults as well. They include:

- Chronic diarrhea or steatorrhea (fatty, foul-smelling stools that float)

- Abdominal bloating and distension

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Nausea and vomiting

- Constipation (less common, but possible)

Non-Gastrointestinal (Systemic) Symptoms

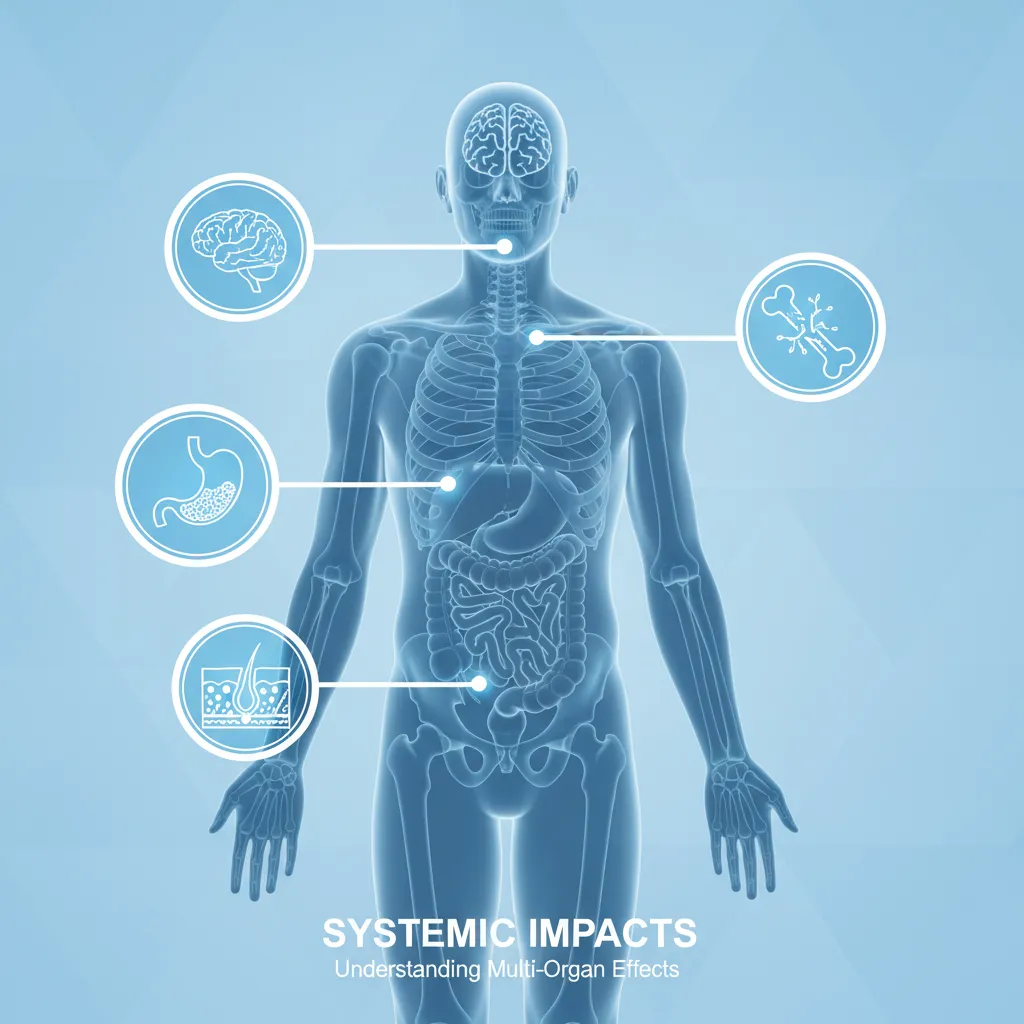

In adults, it is increasingly common for celiac disease to present without any digestive symptoms. Instead, the systemic effects of malabsorption and inflammation take center stage. These include:

- Iron-deficiency anemia: Often unresponsive to oral iron supplementation due to poor absorption.

- Osteopenia or Osteoporosis: Early onset bone density loss due to calcium and Vitamin D malabsorption.

- Neurological issues: Including peripheral neuropathy (tingling in hands/feet), ataxia (balance problems), migraines, and “brain fog.”

- Reproductive issues: Unexplained infertility, recurrent miscarriages, and delayed puberty.

- Dermatitis Herpetiformis: An intensely itchy, blistering skin rash that affects elbows, knees, and buttocks. This is considered the cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease.

How is Celiac Disease Officially Diagnosed?

The importance of a formal medical diagnosis cannot be overstated. Simply adopting a gluten-free diet without testing can lead to a false sense of security or unnecessary dietary restrictions. Furthermore, once a patient removes gluten from their diet, the diagnostic tests become invalid because the body stops producing the antibodies and the intestine begins to heal.

Step 1: Serology (Blood Tests)

The first step in diagnosis is a blood panel to screen for celiac-specific antibodies. The most sensitive and specific test is the Tissue Transglutaminase IgA (tTG-IgA). For this test to be accurate, the patient must be consuming gluten daily. If the tTG-IgA is elevated, it strongly suggests celiac disease.

In cases where a patient has a total IgA deficiency (common in celiac patients), the lab may run a Deamidated Gliadin Peptide (DGP-IgG) test instead. Genetic testing for HLA-DQ2/DQ8 can also be used to rule out celiac disease; if a patient lacks these genes, it is virtually impossible for them to have the condition.

Step 2: Endoscopy and Biopsy

While blood tests are excellent screening tools, the “gold standard” for diagnosis remains an upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy. During this procedure, a gastroenterologist inserts a small camera down the throat to visualize the small intestine and takes multiple tissue samples.

These samples are examined by a pathologist under a microscope to check for villous atrophy. The severity of the damage is often graded using the Marsh Classification system:

- Marsh 0: Normal mucosa.

- Marsh 1: Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (inflammation) but normal villi.

- Marsh 2: Crypt hyperplasia.

- Marsh 3 (a, b, c): Partial to total villous atrophy. This confirms the diagnosis.

What Are the Risks of Untreated Celiac Disease?

Leaving celiac disease undiagnosed or failing to adhere to a strict gluten-free diet carries severe long-term health risks. Chronic inflammation and malabsorption can lead to conditions that are difficult or impossible to reverse.

Malignancy: There is an increased risk of certain cancers, particularly intestinal lymphoma (EATL) and small bowel adenocarcinoma, in patients with untreated celiac disease. Strict dietary adherence significantly reduces this risk over time.

Autoimmune Comorbidities: Celiac disease shares genetic pathways with other autoimmune conditions. Patients are at a higher risk for developing Type 1 Diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and autoimmune hepatitis. Early diagnosis and management of celiac disease may help reduce the systemic inflammatory burden.

Refractory Celiac Disease: In rare cases, the intestine fails to heal despite a strict gluten-free diet. This condition, known as refractory celiac disease, requires specialized medical management, often involving immunosuppressive medications.

Ultimately, celiac disease is a manageable condition. The only treatment is a lifelong, strict gluten-free diet. This involves avoiding all foods containing wheat, rye, and barley. With proper management, the intestinal damage can heal, symptoms can resolve, and patients can lead healthy, active lives. Understanding the medical fundamentals is the first step toward effective management and advocacy.

People Also Ask

Can celiac disease go away on its own?

No, celiac disease is a lifelong autoimmune condition. It does not go away, and there is currently no cure other than a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet. Even if symptoms disappear, ingesting gluten will still cause internal damage.

Is celiac disease the same as a wheat allergy?

No. A wheat allergy is an immune reaction to proteins in wheat that causes allergic symptoms (hives, breathing trouble) immediately. Celiac disease is an autoimmune reaction that damages the small intestine over time and can be triggered by wheat, barley, and rye.

What happens if a celiac eats gluten once?

Even a single exposure to gluten can trigger the autoimmune reaction, causing damage to the intestinal villi. Symptoms may occur within hours or days and can last for several days. Long-term health depends on avoiding these exposures.

Can you be celiac without symptoms?

Yes, this is known as “silent celiac disease.” These individuals have the same intestinal damage and positive blood tests as symptomatic patients but do not experience outward digestive or systemic symptoms. They are still at risk for long-term complications.

How long does it take for the gut to heal after going gluten-free?

Healing time varies. Many patients report symptom improvement within weeks, but complete histological healing of the intestinal villi can take anywhere from six months to two years, and occasionally longer in older adults.

Is celiac disease genetic?

Yes, celiac disease is hereditary. You must carry the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 gene to develop the condition. If you have a first-degree relative with celiac disease, you have a 1 in 10 chance of developing it.